Booker T. Washington National Monument celebrates the life of a man who was born enslaved but became a renowned educator/Jennifer Bain

It’s 10 a.m. on a Saturday and the visitor center at Booker T. Washington National Monument is temporarily closed, albeit for an unusual reason. “The Park Ranger is down in the Historic Area taking care of the animals,” an apologetic sign explains. “They will return soon.”

I wander down the grassy hill and say hello to three chickens, one rooster, two ducks, one horse and two plump pigs who stand expectantly in front of empty troughs. There’s no sign of the ranger, but several sheep graze blissfully in the distance behind a few fences.

This was once a tobacco plantation where Booker Taliaferro Washington was born into slavery and lived with his mother and two siblings until he was nine years old. Freed in 1865 after the American Civil War ended, he went on to become a renowned African-American leader and educator.

Inside a reconstruction of the kitchen cabin that Booker T. Washington lived in for his first nine years as an enslaved person/Jennifer Bain

Washington’s mother Jane was the cook on James Burroughs' plantation and the family lived in a one-room kitchen cabin. The shockingly small log cabin (about 14 by 16 square feet) has been reconstructed and so have other buildings and heirloom gardens from that era, but the woods, streams and fields are the same. Enslaved people often escaped into the woods to meet, relax, fish, forage for food and even worship away from the watchful eyes of their enslavers, who whipped, beat and abused them and made them fearful that the woods were full of army deserters.

The farm, 207 acres at the time, was more than half forest. It's in the rolling hills of the Virginia Piedmont, a half-hour drive from where I stayed at the Liberty Trust in downtown Roanoke in Virginia's Blue Ride region to tackle the Appalachian National Scenic Trail and drive the Blue Ridge Parkway.

“I think I owe a lot of my present strength and ability to work to my love of outdoor life,” Washington once said. The quote is emblazoned on an interpretive sign along the Jack-O-Lantern Branch Trail, which gets its name from a creek or “branch.”

An interpretive panel and bench along Jack-O-Lantern Branch Trail at Booker T. Washington National Monument in Virginia/Jennifer Bain

For 45 meditative minutes, I walk the 1.5-mile loop, listening to birds, learning about sycamores and other local trees, and reading about “forest citizens” like snakes, poisonous plants and insects that bite and sting. I think about what life must have been like for a young Washington, who was fed scraps (bits of bread, scraps of meat, a cup of milk here and a potato there) instead of meals and forbidden from learning to read and write.

By the time I make my way back to the visitor center, ranger Betsy Haynes has returned from doing her farm chores.

She’s running the show alone this weekend, and that means caring for the animals, working at the visitor center and running its book store. We chat in between groups of Girl Guides and other waves of visitors who arrive to see a 13-minute film, Measure of a Man, peruse interactive exhibits and then stroll the grounds on self-guided tours.

Betsy Haynes is a ranger at Booker T. Washington National Monument/Jennifer Bain

“We depend a lot on volunteers at this park,” Haynes admits, telling me to speak with the non-profit Friends of Booker T. Washington National Monument. “Our gardens are basically managed by the volunteers, and a lot of volunteers help with the farm. We all take turns mucking the sheep stalls. So I’m the public affairs officer but I’m also the person that mucks sheep stalls and runs the bookstore here.”

On the day I visit in May, chief interpretation officer Timothy “Timbo” Sims is about to retire and a new superintendent, Jim Bailey, is poised to start but also runs Appomattox Court House National Historical Park 65 miles away. Haynes is waiting to hear whether they’ll get two summer staff or just one. She’s not yet sure how they’ll mark Juneteenth, the June 19 federal holiday that commemorates the emancipation of enslaved African Americans.

Resources are clearly stretched here and staff have been grappling with the question of whether to continue to farm, something that Sims had a special passion for in his 34 years here. For now, the farm remains part of the long-range interpretive plan, even if it means feeding the animals twice a day, making sure they have clean water and coordinating vet care.

One of the two pigs that lives at Booker T. Washington National Monument, a former tobacco plantation that had 10 enslaved workers/Jennifer Bain

“To me — this is my opinion — Booker T. Washington didn’t live in that cabin all the time,” stresses Haynes. “He lived outside, pretty much, if you think about it, and so he was outside with the farm animals. That was his life. So to me, having the farm down there makes it more real. But it’s a lot of work to be able to manage it.”

Before the pandemic, there was a tobacco field here to help tell Washington’s story, but it has to be hand-watered and cared for and that’s a challenge with current staffing levels. Now it’s just an overgrown, fenced space. So is a corn field.

One thing the park does have going for it is an impressive number of interpretive signs, both inside the visitor center and throughout the grounds. In 2022, it reported 20,396 visitors.

Inside the visitor center you can watch a short film and view an exhibit about Booker T. Washington's life/Jennifer Bain

“It is a really small park with a really large story,” says Haynes, who is celebrating her 34th year here as well. “There are not a lot of national parks that focus on the slave story. It’s becoming more relevant in today’s time, but when I started here it wasn’t really focused on so much. You’ve got president’s homes and all that. You always have the focus on the big house or the grand house, but you don’t have the focus on the slave cabin.”

This was once the plantation of James Burroughs, but when he died and his sons went off to war, his widow Elizabeth was left in charge. There were at least 10 enslaved people, including young Washington who was valued at $400 on a property inventory.

There are ongoing debates about whether to reconstruct the Burroughs house — perhaps as a 3D structure — but for the now the feeling is that it would detract from Washington’s story. Then again, Haynes muses, “there’s the question of whether we are missing the balance of power between the owners and the enslaved if we don’t rebuild it.”

A reconstruction of the kitchen cabin where Booker T. Washington lived as an enslaved child until he was nine/Jennifer Bain

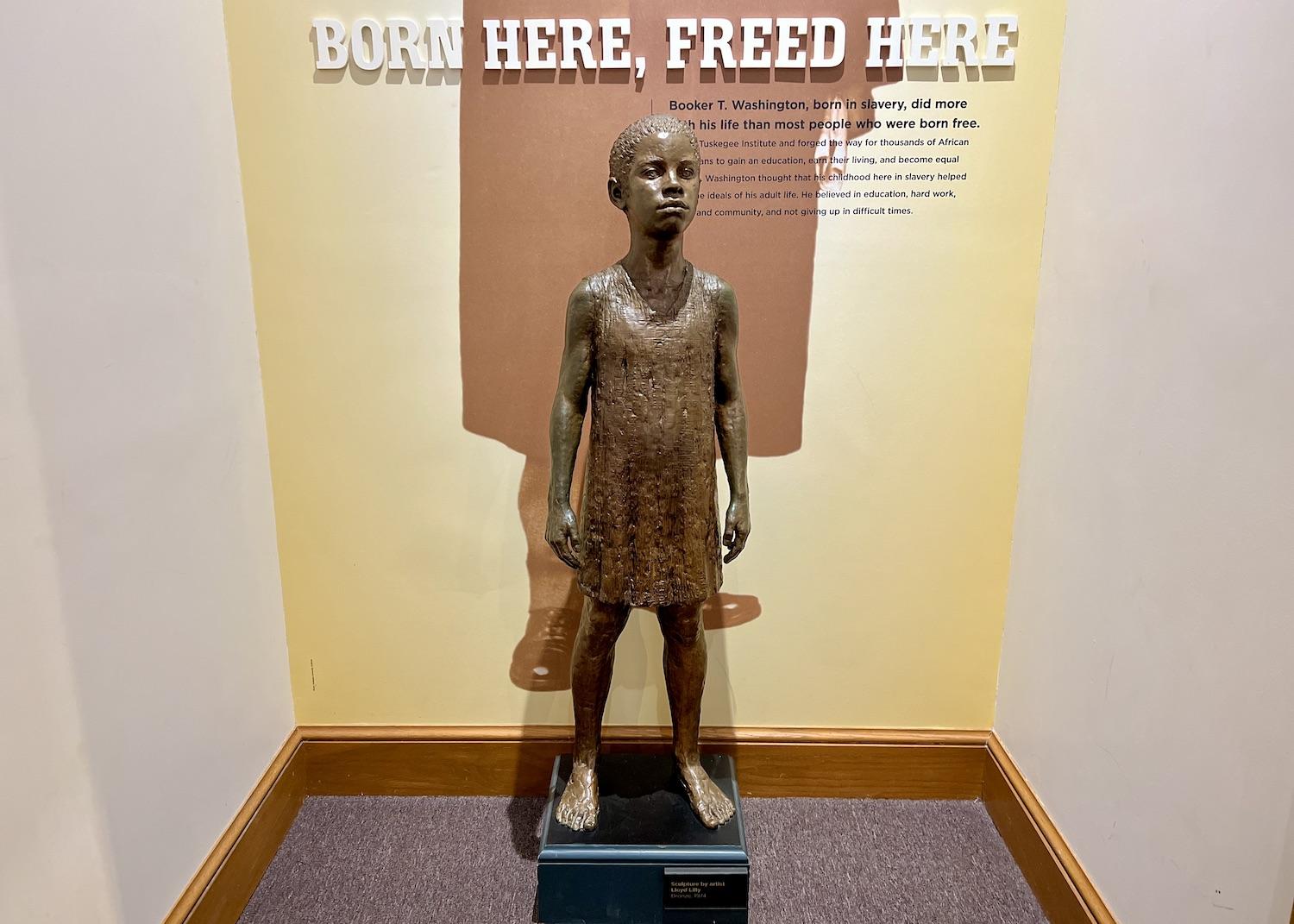

With the southern defeat in 1865, the Emancipation Proclamation issued in 1863 was enforced to free millions of enslaved people. Washington listened to a Union soldier read the document on the porch of the Burroughs house — a moment that is captured with a bronze statue on display at the visitor center. The Burroughs lost most of their "wealth" when they lost their enslaved workers.

Washington's family then moved to Malden, West Virginia to be with their stepfather Washington Ferguson, but even then the boy who was eager to learn was made to work in the salt and coal mines. (Washington didn’t know who his birth father was, but believed it to be a white local farmer.)

Determined to get an education at any cost, Washington taught himself to read and was eventually allowed to go to school after work. He graduated from the Hampton Institute with honors, taught for a spell and was then asked to head a new school in Tuskegee, Alabama.

In 1881, at the age of 25, Washington opened the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University). Students built the first building using bricks they made themselves. Washington married three times and had three children.

Booker T. Washington has been honored on stamps and coins/Jennifer Bain

In 1895, Washington famously delivered the Atlanta Address at the Cotton States and International Exposition, urging citizens of both races to work together toward social peace. He was given an honorary degree from Harvard University, advised government on race relations, founded the National Negro Business League, dined at the White House, had influential friends, wrote several autobiographies, did fundraising and public speaking tours, and lifed up the lives of countless African Americans.

Washington died at home in Tuskegee in 1915 at the age of 59.

In 1940, Sidney Phillips, one of Washington’s former students at Tuskegee, bought the former Burroughs plantation and developed the site as a memorial. Some of the land was donated to create a segregated school for black children that operated from 1964 to 1966. In 1956, the National Park Service took over.

The site now protects 239 acres of fields of grasses and clover, woodlands and a forest that's mainly second growth maturing pine and a variety of hardwood species, according to the NPS. The park also manages more than 3.5 miles of streams, mainly in Jack-O-Lantern Branch and Gill’s Creek. More than 200 species of vascular plants have been documented, plus 26 mammal species, 122 species of birds, nine amphibian species, nine reptile species and 38 species of fish.

Booker T. Washington is popular with dog walkers and people who like to walk the Jack-O-Lantern Branch Trail through woods and this meadow/Jennifer Bain

“This park would be just a drive-by place if the volunteers didn’t get to help out,” says Sheridan Brown, a retired principal and Living History Guild member who’s with the Friends of Booker T. Washington National Monument. She wrote The Viola Factor about Viola Knapp Ruffner, a teacher whose family employed Washington as a houseboy and who befriended and mentored him.

The tranquil park is popular with dog walkers and people taking wedding, family and prom photos. The Friends group hosts an annual legacy dinner to raise money for scholarships. Brown tells me that the park's horse is 32 years old and named Ice Man, the rooster is named Walter and the pigs — Gloucestershire Old Spots — are sisters named Emmy (Emancipation) and June (Juneteenth).

The Sparks Cemetery isn't marked but it's in the woods near Stop 8 on the Jack-O-Lantern Branch Trail/Jennifer Bain

One place that visitors often miss — unless they pick up the Jack-O-Lantern Banch Heritage Trail pamphlet — is the small, unmarked Sparks Cemetery near Stop 8. "The simple fieldstones do not tell us much about those who may be buried here," the pamphlet says, "but slaves frequently used forested ridges like this for their cemeteries."

Last year, the park asked for the public's help to unravel the mystery of the cemetery with dozens of unmarked graves. The Burroughs family cemetery is another part of the park and this one is name for a family that owned the property before them. These graves are believed to be from the 1800s. One has a date on it and seems to say "SID" and "here." But SID could also be "S and D" which could point to previous owner Jesse Dillon Sr., whose family sold the property to the Burroughs.

Archaeologists from New South Associates came and investigated with devices using electric resistivity and ground-penetrating radar. The park now suspects at least 41 people (possibly of both races) are buried here, but there is much more work to be done — when and if budgets and staffing levels allow.

You can make out a date and a few letters on this tombstone in Sparks Cemetery/Jennifer Bain

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places